First image of a black hole's "shadow" may be possible soon

Slight advances could make event horizon of Milky Way's central black hole "visible"

A "picture" of the massive black hole thought to be lurking at the heart of our home galaxy may be within astronomers' reach in the next few years, according to a report in the Jan. 1, 2000 edition of Astrophysical Journal Letters. The paper predicts that upcoming improvements in scientific techniques could permit astronomers to see how a narrow escape from the black hole's clutches twists, dims, and amplifies radio waves.

The event horizon is thought to be the defining feature of a black hole, a point-of-no-return surrounding the hole inside which even light cannot escape the black hole's gravity. Imaging this would be a final step in the black hole's journey from curious theoretical oddity to cosmic reality.

"Regardless of the structure of the region around the black hole that we tried in our computer models, we saw a shadow in the simulated images," says Eric Agol, a postdoctoral researcher at Hopkins and an author of the paper. "This paper is our way of trying to interest astronomers in working together to perform the actual observations, which could produce very exciting results."

Agol cautions that the same plasma that emits radio waves near the black hole might also block the radio waves needed to "see" the hole an effect not included in the models. This could be circumvented by observing at even shorter wavelengths where the plasma becomes transparent and the black hole shadow will appear. "This would make it harder to see it from the ground, but it should always be possible to see it from space," Agol says, noting that some shorter wavelengths are blocked by Earth's atmosphere.

So far scientists have only been able to indirectly detect black holes by observing their effects on the orbits of nearby stars or by detecting the powerful radiation given off by gas and other material being pulled into the black hole.

Astronomers have seen these effects in the centers of other galaxies. The Milky Way's center can't be seen in visible light because there's too much interstellar gunk in the 25,000 light years between Earth and the galactic center. But longer-wavelength radiation like infrared radiation and radio waves can make it through relatively unscathed.

"At Sagittarius A star [Sagittarius A*], a point at or near our galaxy's center, astronomers have found a compact source of very strong radio emission, perhaps created by highly ionized gas surrounding a black hole," says Heino Falcke, research scientist at Max-Planck-Institut and lead author on the paper. "Infrared observations of the same region show rapidly moving stars pulled around by a very concentrated mass at the same position as the radio source Sagittarius A*. This is probably the best evidence that we have for a black hole so far, but not decisive proof."

To zoom in further on the radio wave emission in this area, scientists have used a technique known as Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI). By coordinating and comparing the results they receive from different radio telescopes, they can produce an image with greater detail and resolution than the individual radio telescopes could on their own.

"The resolving power is equivalent to what you'd get if you had a radio telescope as large as the telescopes you're combining and the area between them," says Falcke. "This can be as large as the size of the Earth."

Astronomers at the Max-Planck-Institut and elsewhere have been working to use VLBI to observe shorter wavelengths of radio emission, a technique known as millimeter-VLBI. By pushing VLBI to the shortest wavelengths and highest spatial resolutions available in astronomy, they have already come very close to the resolution that should be needed to see the shadow.

"I think we didn't realize before how close the technique is to detecting this shadow," Falcke says. "With the currently available resolution, we could =91see' from Berlin Germany a radio source in Los Angeles the size of a mustard seed. Now we have to improve things just to the point where we can image a dent on the seed."

"The improvements necessary to test this prediction are within reach and should become feasible over the next few years," says Anton Zensus, director at the Max-Planck-Institut and leader of the VLBI group.

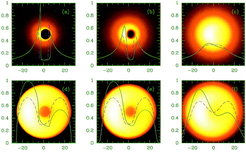

For the paper, the authors took what astronomers currently know about the mass of Sagittarius A* and plugged it and other potential features of the black hole, such as its rotation, into a "relativistic ray-tracing" program Agol had developed. The program traces the path of electromagnetic radiation through space warped by the tremendous gravity of a black hole.

"You can think of it as taking each photon of radiation emitted somewhere near the black hole and following its path to the observer," explains Fulvio Melia, astrophysicist from the University of Arizona and co-author on the paper. "The program calculates the effects of the black hole on the radiation's path and wavelength, effects that are very precisely predicted by Einstein's Theory of General Relativity."

"A similar, simplified calculation was made by physicist James Bardeen in the 1970s," says Agol. "At that time, we didn't have as much information on the galactic center, so his work was considered by many to be a purely theoretical exercise."

Given the resolution achievable at short radio wavelengths, the new calculations showed a distinctive pattern in radiation from Sagittarius A*: a circular shadow.

"With the major observatories working together, and a further improvement of millimeter-VLBI, we should soon be able to actually image the shadow of a black hole. This would be the final test of whether black holes and event horizons exist," says Falcke.

Since demand is high for time at radioastronomy observatories, he acknowledges, that would take no small amount of money, effort and sacrifice. But because of the potentially tremendous step forward this effort might produce, he and the other authors strongly feel the challenge is worthwhile.

----------------------------------------------------

This research was supported by grants from NASA, DFG (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft), the National Science Foundation and a Sir Thomas Lyle Fellowship (F. Melia).