A black widow's Tango Mortale in gamma-ray light

Max Planck scientists discover record-breaking millisecond pulsar with new analysis method

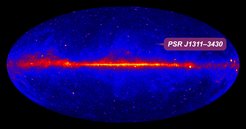

Back in 1994, astronomers discovered a source of strong gamma-rays in the constellation of Centaurus. They suspected that a pulsar was the origin of the energetic radiation. Now, a team of scientists led by Holger Pletsch from the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics (Albert Einstein Institute, AEI) has solved the mystery and identified the culprit: the millisecond gamma-ray pulsar PSR J1311-3430. The development of a new data analysis method by the AEI scientists enabled the discovery, since rapidly spinning pulsars are extremely difficult to find.

To unambiguously identify a gamma-ray pulsar, astronomers must know its properties to very high precision. This includes its position, spin frequency, and how the latter changes over time. If the pulsar is in a binary system, the analysis problem is even more complicated: at least three additional orbital parameters have to be determined as well.

In the case of PSR J1311-3430 astronomers had already observed the companion, which is heated by the radiation from the pulsar, with optical telescopes. They were thus able to partially constrain the orbital parameters and confine the position of the pulsar.

“We developed a particularly efficient method to search the data from NASA’s Fermi satellite for gamma-ray millisecond pulsars, including those in binary systems. Only this method enabled us to probe the wide parameter ranges,” says Holger Pletsch, lead author of the article published in Science. The new analysis method enables scientists to conduct a 'blind search' for gamma-ray millisecond pulsars for the first time – right up to very high spinning frequencies.

The scientists analysed the Fermi data on the Atlas computer cluster at the AEI. “Our search used data collected by the gamma-ray satellite over a total of four years. Very soon after we started running the analysis, a clear signal showed up in the results. What we saw was very exciting,” says Pletsch.

PSR J1311-3430 spins 390 times per second, emitting gamma-ray photons into space in the form of a beam, similar to a lighthouse. In roughly one in a million revolutions of the pulsar, a single photon reaches the detector on board Fermi.

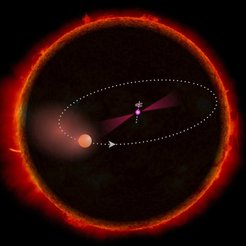

The gamma-ray signal also reveals much about the companion to the astronomers: the orbital motion of the binary system modulates the photon arrival times, yielding information about the partner star. “The companion object is small and unusually dense,” says AEI Director Bruce Allen. “It is at least eight times as massive as the planet Jupiter, but has at most 60 percent the planet's radius.”

From this information, the researchers calculated the density of the companion, which turned out to be unusually high; it is around 30 times as dense as the Sun. Presumably, the small companion is the compact remnant of a star which has been orbiting the pulsar since earlier times. Over time, the pulsar accreted matter from the star, thereby accelerating its rotation. Pulsar and companion moved closer and closer together.

“At present, the remaining stellar core, which presumably consists mainly of helium, is heated by the radiation from the pulsar and literally evaporated,” says Holger Pletsch. Astronomers call this type of pulsar a 'black widow', in analogy with a species of spider which kills the smaller male after mating. In the distant future, PSR J1311-4330 might possibly completely vaporize its companion and from then on travel through space alone.

And that’s not all: “Our discovery is not only a first, it also sets several new records,” explains Bruce Allen. Currently, the odd couple is orbiting its common centre of mass on an almost perfect circular trajectory in only 93 minutes. This is the shortest known orbital period of all pulsars in binary systems.

At a distance of only 1.4 Earth-Moon separations, the binary system is the closest one known to date with a pulsar. The pulsar is speeding along its circular orbit with at least 13,000 kilometres per hour. Its light-weight companion is even faster, at up to 2.8 million kilometres per hour.

Holger Pletsch and his colleagues also had a close look at older observations with the Green Bank radio telescope in West Virginia, but were unable to find the fast pulsar here. “Apparently, the cloud of vaporized material from the companion absorbs most of the radio wave emissions from the pulsar and possibly makes it invisible to radio telescopes,” says Lucas Guillemot from the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn, co-author of the publication. The scientists are already planning further observations at higher radio frequencies. They hope to use them to accurately determine the object’s distance from Earth, for example.

Systems like this provide astronomers with new insights into the evolution of very close binary systems, which are as yet still incompletely understood. PSR J1311-3430 could also shed new light on the generation of the gamma-ray photons and radio emissions in the strong magnetic field of pulsars. The pulsar may just be the tip of the iceberg: many other unidentified gamma-ray sources may harbour similarly unusual systems. Thirty years after the discovery of the first millisecond pulsar in the radio range, the novel analysis method of the Max Planck researchers at the AEI has opened a new door to the easier identification of these elusive celestial objects.

KNI / ME / HOR